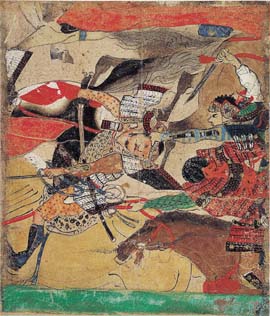

Ink and color on paper

Kamakura period, 14th century

Heiji monogatari (Burke Collection)  Heiji monogatari (MIHO MUSEUM) |

The original version of the Battle at Rokuhara scroll was lost by the late Edo period, and at some point, into segments. An ink copy in the Tokyo National Museum verifies the various existing segments of this handscroll, which corresponds to the incidents of the Rokuhara Battle and the defeat of Minamoto no Yoshitomo from the Tale of the Heiji Civil War and includes the climatic scenes from the rebellion.

From the Tokyo National Museum ink copy, it can be seen that the lower right section of the Burke segment, depicting the decisive battle at Sanjô Kawara, corresponds to the MIHO segment. On the upper section between the two paintings was originally a segment depicting Taira no Kiyomori, in green armor, charging ahead. In the Burke segment, two Taira warriors attack their Minamoto opponent-one grabs the crupper of his opponent’s horse as another takes hold of the opponent’s helmet to cut his head with a small sword. The embattled Minamoto warrior tries to draw his sword in retaliation. The MIHO segment captures a Taira warrior, spurring ahead a his white horse with a long halberd in hand, below a red flag that symbolizes his clan, attended by an armored soldier, ready for bloodshed as if to attack this opponent.

Sanjô Kawara area is transformed into a bloody battlefield as Kiyomori’s force swept away everything in their path to pursue their enemy Minamoto no Yoshitomo and Yoshihira. The tension can be felt in even these small segments. At the same time, these battle scenes are highly romanticized. This colorful handscroll emphasize pictorial depiction and visual effect over textual content, and it is perhaps these vivid and colorful images that attracted both collectors to these works.

Hotei By Ogata Kôrin Hanging scroll, Ink on paper Edo period, 18th century

Daikoku By Ogata Kôrin Hanging scroll, Ink on paper Edo period, 18th century

The genius of painter Ogata Kôrin (1658-1716) perhaps can best be seen in ink paintings such as this. Kôrin painted numerous images of Jurôjin, Daikoku, and Hotei from among the seven gods of good fortune, which appear to have been painted all about the same time. These examples were not limited to his paintings, also depicted these themes in underglaze iron on rectangular plates, made by his potter brother Kenzan. In these many works, Hotei is depicted in some unusual guise, such as playing kickball or on horseback.

Hotei (Burke Collection) |

Daikoku (MIHO MUSEUM) |

This painting has Hotei seated next to his large bag and leaning his right elbow on it. Several other similar compositions, though with different signatures and seals, can be seen in the Schlenker, Feinberg, and other collections. Here, we get a glimpse of Kôrin’s distinctive brushwork, combined with a quick, light touch and keen design sense, in his use of three different ink shades, in the details of his garment, staff, head, and shoulder.

Hotei, or Budai in Chinese, was a monk who lived in the Five Dynasties period of China. He is known for his fat belly and for carrying all his worldly goods with him in a large cloth bag, hung around a staff. Wandering from town to town, he was called “Budai Heshang” (lit., “Cloth-Bag Priest), and came to be seen as an incarnation of the future Buddha Maitreya. Often the subject of Zen ink paintings, Kôrin’s Hotei here, in comparison with more religious works, appears quite secular. Indeed, the work has a sense of humor and familiarity that add to its viewer’s enjoyment. The work is signed in the lower left, “Jakumyô Kôrin,” and stamped with a single square intaglio seal that reads “Dôsû.”

Daikokuten was originally the Indian god of war, Mahâkâla (“Great Black”). When he was introduced to Japan in the Heian period, he was still considered a wrathful deity. His early image was associated with esoteric Buddhist iconography, such as seen in the Womb World Mandala. However, in Muromachi period (1392–1573), he came to be identified with the Shinto deity Ôkuninushi no mikoto and popularized as one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune. The image of this deity in popular belief portrays him wearing a hood, carrying his mallet of luck in his right hand and a large bag in his left, and sitting on a tightly bound bale of rice. In this painting, Daikokuten is depicted standing with a bamboo staff in his right hand and his mallet in his left, and carrying a bag and rice bale on his back. The year Kôrin produced this work, 1705, marked his second year in Edo (now Tokyo). The lively depiction of the god at his prime with jovial gaze and energetic stance seems to reflect the artist’s own ambitions to make a name for himself in the new capital. Like Hotei, Kôrin executed this witty, yet refined work with swift, light brushwork, while showing great attention to detail in shading the contour lines of the deity’s garment and beard. Here, Kôrin used a different signature, “Hôkyô Kôrin,” on the lower right corner, while he used the same square intaglio “Dôsû” seal.

|

|||

| Saturday, April 15, 2006 at 14:00 p.m. | |||

|

|

|||

| Dr. Nobuo Tsuji, Director, Miho Museum | |||

| Sunday, May 14, 2006 at 14:00 p.m. | |||

|

|

|||

| Dr. Miyeko Murase, Research Curator, Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art | |||