|

|

|

|

This exhibition brings

together over one hundred “smiles” from the early Mesopotamian dynasty

to Japan’s Edo period, covering a period of four millennia. While

dealing with the destructiveness of nature and the austerity of the

gods, humans have earnestly aspired to and shown adoration to the gods,

who brought them to life and blessed them with nature, and also to the

buddhas, who showed them compassion. Come see the “archaic smile” that

reflects the prayers of these people. |

|

The ancients of West Asia created figurines modeled after themselves as

their substitutes, which they offered in their sanctuaries. The tightly

bound hands in front of the chest represent the strength of their prayer

for which they risked their lives in serving the gods. |

|

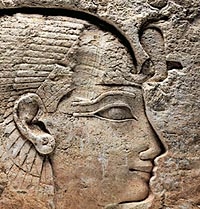

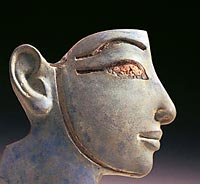

The Egyptian kings and queens were believed to be manifestations of the

gods and thus embodied the cosmic order. The deluge of the Nile, which

was controlled by this order, promised abundant harvests. Graceful

smiles are seen on the images of the kings and queens and of the gods

that represent this nurturing nature. |

|

|

|

||

|

For the Greeks, wooden and stone statues of their divinities, called

agalma (joy, smile), were actually living gods. The nobility created

statues in their own image, which they offered to the gods, but today

many of these cannot be differentiated from statues of the gods

themselves. |

|

|

|

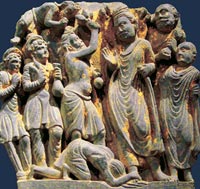

Mahayana Buddhism flourished during the Kushan dynasty, which prospered

from Silk Road trade. Images of Buddhas, which had not been created

until then, appeared during this period. In Gandhara, the influences of

Hellenistic and Roman art took root and the smiles on matured

expressions of transcendent buddhas, compassionate bodhisattvas, and

joyful devotees were produced. |

|

When Buddhist stupas were first constructed in India, images of divine

beings and humans that adorned these structures were expressionless.

Although the influence of Gandharan exchange is not certain, the statues

of buddhas and gods that appeared later in Mathura in central India

clearly have smiles. |

|

|