|

Tokoname

|

|

||

Boasting the largest production among medieval kilns and

greatly influencing the other unglazed ceramic production

sites throughout Japan, Tokoname played the leading role

among medieval unglazed ceramic ware. Rough and rich in

iron, its clay can be nicely fired even at low temperatures

making it suitable for the production of pots and jars. Like

the other kilns that produced unglazed pottery, its main

products consisted of pots, jars, and large bowls. From

Aomori in the north to Kyushu in the south, its pots and

jars were especially in demand across Japan as storage

vessels for fertilizers, grains, and water. The image of its

robust shape with its shoulders swelling out overlaps with

the bold appearance of the warrior, making Tokoname a leader

in medieval ceramics. With developments in agricultural

technology, perhaps such pots and jars provided support in a

time when agricultural productivity, the economic base,

rapidly rose.

|

|

Atsumi

|

|

||

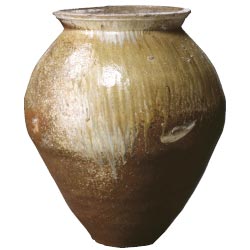

The Atsumi kiln was created on the Atsumi Peninsula,

situated on the opposite shore of Chita Peninsula, where the

Tokoname kilns are located. Here, too, the three types of

vessels—pots, jars, and large bowls—were fired as primary

products. Like other kilns, it is seen as a ceramic

production site that supported agriculture.

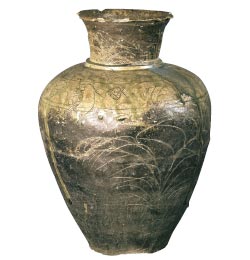

This area also produced ceramic ware used for religious purposes such as the roof tiles for the Kamakura-period reconstruction of Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara and cylindrical jars that were often used as outer containers for sutra cases, which were buried in sutra mounds. Unlike Tokoname ware, pots with incised line drawings can be seen on Atsumi ware. A glimpse of the Atsumi potters’ aesthetic sensibility and rich creativity can be found in these pictorial decorations, such as the famous autumn grass motif (on the pot to the upper right), crossed bands, lotus petals, and heron and reeds. |

|

Echizen

|

|

||

Echizen was greatly influenced by the Tokoname kilns and

flourished in the village of Miyazaki, Nyuu County, Fukui

Prefecture, around the latter half of the 12th century. Its

main products consist of pots, jars, and large bowls, and

because Echizen developed from the introduction of

techniques from Tokoname, its forms closely resemble

Tokoname ware. The similarity of the three-ribbed pot from

the two kilns is especially notable, making it often

difficult to distinguish the two types. Since Echizen clay

is white, of better quality than Tokoname, and has a high

refractoriness, it can be fired at higher temperatures. Its

distinguishing features include tightly fired luster on its

surface and a thick heavy finish.

|

|

Suzu

|

|

||

Like

Echizen, the Suzu kilns were situated on the Japan Sea side,

in a town that was built on the tip of the Noto Peninsula in

Ishikawa Prefecture, in the 12th century. Although Suzu ware

is also unglazed, in contrast to Echizen’s reddish hue,

created in oxidation firing, the surface of Suzu ware turns

gray or black due to reduction firing. Suzu kilns inherited

the tradition of Sue ware that was brought to Japan from the

Korean Peninsula during the Kofun period (250−538), and its

main products—also pots, jars, and large bowls—were created

using the paddling (J., tataki) technique. A unique

aesthetic sensibility—such as the decorative elements of

zigzag patterns created by paddling, trees, and crossed

bands, as well as lugs—can be seen in Suzu ware. Religious

works, such as this five-tiered stupa (on the right), also

can be found.

|