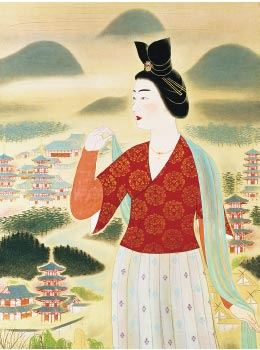

Kawabata and Yasuda came to appreciate Japanese culture and its spirit all

the more through their encounter with early Japanese art and felt a need to

connect this to the future. The Japanese culture that these two artists felt

and left behind represents the beauty of Yamato, the Japanese ideal.

When the war became increasingly miserable, I often felt the old

Japan in the shadow of the pine trees on a moonlit night. War saddened me

rather than angered me. I felt desperately sorry for Japan. I, while on

watch for an air raid, stood still on the street chilled by the night, and

felt my sorrow and Japan’s sorrow melting into each other. The old Japan

streamed through me.

I should live, I wept. I thought that there would be the beauty of perishing in my dying. My life is not owned only by myself. I thought that I would live for the tradition of the beauty of Japan.

I should live, I wept. I thought that there would be the beauty of perishing in my dying. My life is not owned only by myself. I thought that I would live for the tradition of the beauty of Japan.

Okakura Tenshin (1862–1913) once said, “Studying art history is nothing but a description of the past. It is essential to have the materials to create art for the future. Our responsibility—to act as the interim between past and future and to unify them—is grave.” As artists, we must all the more so cultivate the insight to sufficiently understand the art of the old.

When my eyes grew accustomed to the darkness inside the sanctuary, a large twelve-panel wall painting appeared. The decorative composition, the stunning three-dimensional depiction of the Buddha appeared to me like a dream. This is a masterful work. It is the finest, most definitive, and most innovative Buddhist painting. There is nothing like it in Japanese Buddhist painting. It is neither from China nor India. It has the aura of the western regions of China or faraway Europe, but I think this refinement has to be none other than Japanese.